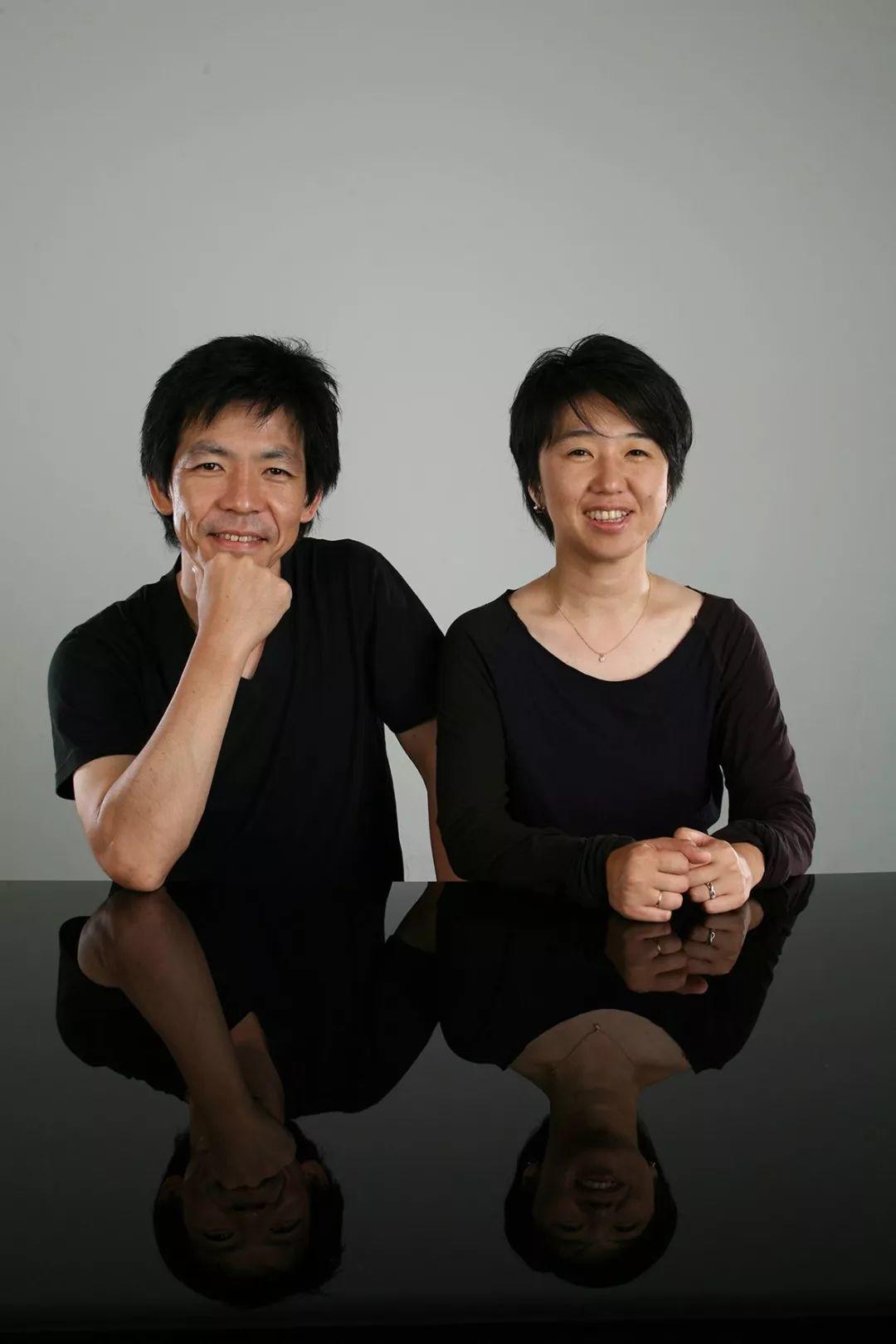

1992年,贝岛桃代和冢本由晴在东京成立了犬吠工作室(Atelier Bow-Wow)。至今,他们的城市研究,尤其是有关微型/临时城市空间的研究,已开展了27年之久。在这长期的探索过程中,犬吠特有的城市理论和记录绘图方式日趋深刻成熟。原本被视为先锋的他们,在学界和业界形成了越来越大的影响。

Atelier Bow-Wow, the Tokyo-based architecture firm founded by Yoshiharu Tsukamoto and Momoyo Kaijima in 1992, is well-known for its urban research and theories that explore micro and ad-hoc architecture in cities through drawing and typological study. Kaijima names Bow-Wow's approach as "Architectural Ethnography", which employs fieldwork and observation to grasp qualities of spaces and ways people use them. “Architectural Ethnography” explores the potential of architectural drawing as a tool to study people and society based on their regional and cultural differences.

贝岛将犬吠的研究方法称为 “建筑民族志”(Architectural Ethnography),意在将实地考察和观测摆在城市研究的重要位置,从而通过当地人,而非建筑师和规划者的视角,去了解人们的生活环境,最终用建筑绘图的方式,将具有地域特色的研究表现出来。

According to Kaijima, the methodology entails “observing and drawing architecture and urban space from the viewpoint of the people who use it, rather than the architects and planners who are involved in its construction.”

访谈中,贝岛提及她长期以来对生活和建筑间关联的巨大兴趣。她想知道,“建筑究竟如何影响生活在其中的人和他们的生活方式?”。基于这一兴趣,她和冢本才开始对东京进行调研。而后诞生的《东京制造》(Made in Tokyo)和《宠物建筑》(Pet Architecture)等研究、出版及展览成果, 使得犬吠在建筑学界和行业内形成了很大影响。他们的线描制图方式,以及类型学研究方法,亦由此成为各大建筑院校学生效仿的对象。

During the interview, Kaijima acknowledged her longtime interests in the relationship between life and architecture. "How architecture affects the lives lived around it" has been a central question which led to her founding of the research group with Tsukamoto and their investigation of urban space in Tokyo. The research turned into publications and exhibitions, such as Made in Tokyo, Pet Architecture, and had a great influence on the architectural academia and profession.

作为同样从事城市研究的后辈,我们对探索建筑的形式,以及形式与人的栖居之间存在的联系也极富热情。除却对犬吠的绘图表现形式抱有浓厚兴趣,我们更想知道的,则是这些图画背后的思考。

As followers who are also passionate about this relationship between architectural form and human occupation, while we are exploring urban environments and ways of their representation, we are curious about the thinking process and concerns behind Bow-Wow's representation rather representation itself.

对话过程中,贝岛表达了她的担忧。她认为,数码时代下的电脑绘图会给设计和城市空间带来很大的危机。

During our conversation, Kaijima mentioned about her concerns for the architectural and urban crisis brought by digital tools like computer.

尽管轻而易举的复制与粘贴仿佛提高了设计的效率,3D的虚拟建模也好像赋予了塑形无穷的可能性,然而,手绘制图中每条线背后的深思熟虑以及设计对人的关怀,在当今时代却越发罕见了。

Easy copy and paste seemly increase efficiency of design; 3D modeling seemly creates infinite possibilities in building form; yet the well-thought process and the humanistic concern existing in hand drawing has gradually disappeared.

“为什么这么画?为什么这条线重要?图面的限制在哪里?有哪些元素没有被包括进来?为什么?”

"Why do you draw this line? Why is it important? What are the limitations? What are the missing elements? Why?"

贝岛的这些问题是她留给学生,乃至广大建筑行业从业者的。对她来说,建筑设计应当少画而多思,因为对于一个概念的深入思考,远胜于一百个未经推敲的想法。

These questions raised by Kaijima for her students are also important for architectural practitioners like us to answer. She addressed that architects should draw less and think more, as an in-depth exploration of one design surpasses one hundred arbitrary ideas.

面对当今建筑的产业化、快速度及其所引发的焦虑,面对中国以至全球范围内令人担忧的城市环境,建筑师兴许应当如贝岛所说,试着慢下来,去观察,去思考。

“为什么设计? 为谁而设计?”

As Kaijima noted, faced with the unprecedented speed and anxiety of the architectural profession, as well as the worsening urban environment in China and around the world, architect might need to slow down to observe and to think about questions like "why do we design? Who are we design for?"

提出这些问题,将是开始转变的第一步。

The kind of thinking is probably the first step for changes to happen.

Jingqiu “建筑民族志”“建筑行为学”这些批判性概念,源于社会学和人类学等其他学科,犬吠跨学科的研究通常是怎么形成的?这背后的思考是什么?

Jingqiu: Architectural Ethnography / behaviorology, those critical concepts relate to sociology and anthropology, how does Bow-Wow usually formulate research or concepts that are not limited to architecture but cross-disciplinary? What are the intentions behind?

Kaijima 我是一个建筑师,建筑是我理解社会和世界的重要方式。举个例子,《东京制造》(Made in Tokyo)反映了东京的生活,东京经济的增长方式,以及密度对于建筑的影响。我们发现建筑是其所处社会的映射,空间和建筑是观看社会的重要角度,这便是建筑、民族志以及社会学之间相似的地方。

Kaijima: One simple answer is that I am an architect. Architecture is an important method to understand the condition of society and world. Made in Tokyo is the representation of Tokyo's life that relates to how the economic grows in Tokyo and how density affects architecture. We then found out that architecture could reflect a society and its contexts. That is why ethnography and sociology are similar to architecture.

但从方法论上说,这些学科之间存在一定的区别。社会学使用数据,民族志学者通常使用大量的文字而非图画。有时候,社会学、人类学等学科也会求助建筑师去做建筑部分的研究。

Spaces and buildings are both important lenses to look at society. Methodologically, the disciplines are different: sociology uses data; ethnography normally uses lots of texts instead of drawings; some of them do both and cooperate with architects to integrate architectural parts.

事实上,建筑和这些学科时常相互交叉。例如,在《建筑民族志》中,我还提到,日本在各种灾难之后(战争、地震和海啸),以及在现代化过程中,涌现了几位重要的民族志学家[1],他们中的某些人对于建筑的形式和表达,以及这些现象背后的原因也有极大的兴趣。

We overlap with those disciplines from time to time. For example, in Architectural Ethnography, I also mention important ethnographers who worked in Japan during the modernization or the recoveries after the disasters, such as the wars, the earthquakes, and the tsunamis. Some of them were also interested in how to express and explain their observations in architecture.

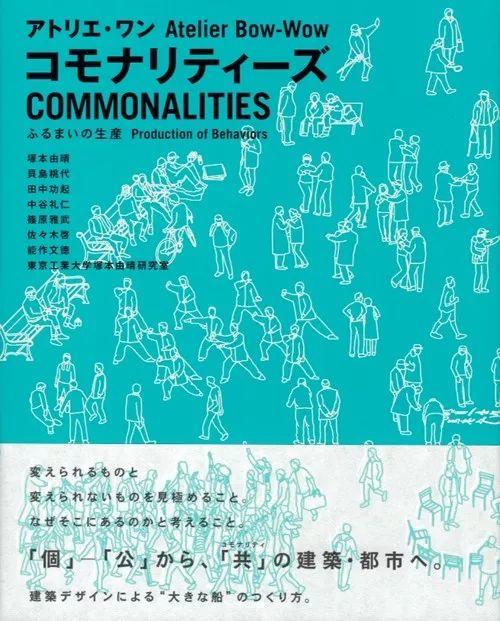

Jingqiu 犬吠2014年出版的《公共性》一书,对建筑的资本化、产业化,还有现代城市中各种文化和社会特征的消失都进行了反思。您能对这本书背后的思考做进一步解释吗?在这样的语境中,每个建筑师作为独立的个体应该扮演什么样的角色?另外,您在之前的演讲中同样提到,对整个行业的重新设计和定义,对此您能更详细地阐释一下吗?

Jingqiu: We read your 2014 book Commonalities, the book responds to capitalism, the production of building industry, and the erase of characteristics in the modern cities. Could you explain more about what is the ultimate goal or intention behind the discussion? How do you imagine the roles of architects and individuals play in this conversation pertaining to the re-designing the industry?

Kaijima 在《公共性》一书中,我们其实有好几个想讨论的话题,其中比较浅显的是关于文化和行为的部分。

Kaijima: Commonalities has several topics, the simpler one is on culture and behavior. Each country has different attitude and behaves differently.

每个地区都有不同的观念和行为,例如在日本,人们总是鞠躬,而在欧洲,人们则习惯于亲吻脸颊和握手。总而言之,人们的行为存在很大区别,这影响着人与人之间的距离,通常是物理距离。当我们走访不同的城市和它们的公共空间时,我们开始逐渐理解,人与人之间究竟是如何互动的,不同的团体之间究竟是如何共享公共空间的。这些文化和身体上自然而然的行为,是设计的重要组成部分。

For example, in Japan, people always bow, whereas in European countries, people cheek kiss and shake hands. These kinds of behaviors are very different, and relate to the distance, sometimes physical distance, between human beings. When we visited several cities and their public spaces, we could then understand how they behave and how they share some spaces amongst different groups.

作为设计师,无论是在城市还是在乡村的语境中,如果我们能够激活和促进行为在公共空间的表达和活力,那么对于各个文化来说都会很有帮助,这也将使设计和空间的使用变得更有乐趣。

I think that the autonomous behavior of a physical body and culture could also be integrated into a design process. If we could activate their behavior to be expressed as a livelier condition in some public or communal spaces, it might also be very helpful to the people or the culture to be more fun and interesting in urban or village contexts.

设计师的角色,就是创造这样的条件,让这些行为发生,像是按下激活行为的“按钮”。在《公共性》中,我们尝试收集不同案例,研究什么样的元素和体验会成为这样的“按钮”,其中包括气候的影响,人们的行为本身,也包括建筑的类型和空间的构成。

Design can be like 'pushing a button' to start a behavior. In Commonalities, we tried to collect different examples that illustrate what kind of elements or experience can be the 'button' to activate behavior, which includes climate, people's behavior itself, and architecture typologies as well as spatial composition.

在书中,我们没有提到具体细节,但这些案例背后的想法,是希望通过用绘图的方式理解人们的行为、行为背后的原因,以及行为和空间之间的关系以及相互的影响。如果我们能理解它,我们就能将这些理解运用到设计中,就能通过设计激活和辅助这些元素,让人们的态度和行为变得越来越有活力。

In the book, we didn't describe the details, but the idea was that through drawings we could understand how people behave, why people behave like that, what effects the connections between behavior and spaces. If we could understand this kind of relational condition and bring them into our design even a bit, we can activate more and more the inhabitants' attitude and behavior.

对任何小元素,我们都可以用这样的思路去考虑,例如在空间中放置质感很好的舒适长凳,亦或是引入美丽的日光。

For example, we could put long benches with nice materials, or introduce very beautiful sunlight into a space.

Jingqiu 犬吠在不同城市设计过很多都市空间,例如运河游泳俱乐部(比利时布鲁日,2015)、宫下公园(东京,2011)、古根海姆实验室(纽约,2011年8月-11月),北本车站(北本,2008年-2012年)。请问犬吠怎样看待不同城市里文化和景观环境的区别?对于不同的场地,通常的设计过程是怎样的?都是从什么角度切入的?

Jingqiu: Bow-Wow has designed urban spaces in different cities such as Canal Swimmer's Club (Bruges, Belgium, 2015), Miyashita Park (Tokyo, 2011), Kitamoto Station (Kitamoto, 2008 - 2012) and Guggenheim Lab (New York, 2011.8-10). How do you deal with different sites with different culture and landscape environment? What is the usual design process? Is there any entry point to the process?

Kaijima 我相信观察的力量。方法是首先尝试理解每个空间和场地背后的语境和原因,而后试着用设计将既有场地中的某些元素最大化。这些元素被我们称为“行为的种子”,它们可能存在于自然环境中,也可能存在于建筑中。

Kaijima: I trust power of the observation. The method is that we understood what the contexts behind the space and the condition are. And then we try to maximize some elements of the condition, the 'seeds of the behavior', in nature and building, through design.

在运河俱乐部的案例当中,游泳就是这样一种“行为的种子”,它存在于历史语境。我们首先发现,五十年以前,甚至更早,人们就有在运河中游泳的习惯,但由于河水在过去几十年间被污染了,政府不再允许人们下河游泳。设计过程中,我们发现近年来河水的水质越来越好,人们又可以回到运河里游泳,而且政府也表现出鼓励这种活动的意愿。如此这般的情形往往是我们实现设计的关键。

In the case of the Canal Swimmer's Club, swimming was in the historical context. We first found out that the behavior of swimming was there 50 years ago. Unfortunately, the canal was polluted in the last 50 years, and the government limited the swimming activities. But we got some good news that recently the water becomes better and better, and people can start to swim, or the government expects swimming activities to return to the canal. And then, this kind of condition is realized by our project.

对于北本车站的设计,当时的场地中已经有很多隐含的“行为的种子”了。比如,车站周围有树林;一些年轻人愿意到车站附近来;当地人也很想在这个地方举行活动、表演甚至筹办市集。我们听到了这些声音和意愿,观察到了这些“行为的种子”,而后便使用设计将其最大化,为“种子”的“生根发芽”作准备,像是在创造激活相应行为的“按钮”。

In the Kitamoto case, there are several 'seeds' have already existed: the element of the forest was around the station; some young people wanted to visit the station square; some local people want to show their activities by performing in front of the station or they want to have a market. We heard these kinds of voices or observed these kinds of conditions as the 'seeds' of the place and then we maximize them, or we prepare for them, like making a 'button'.

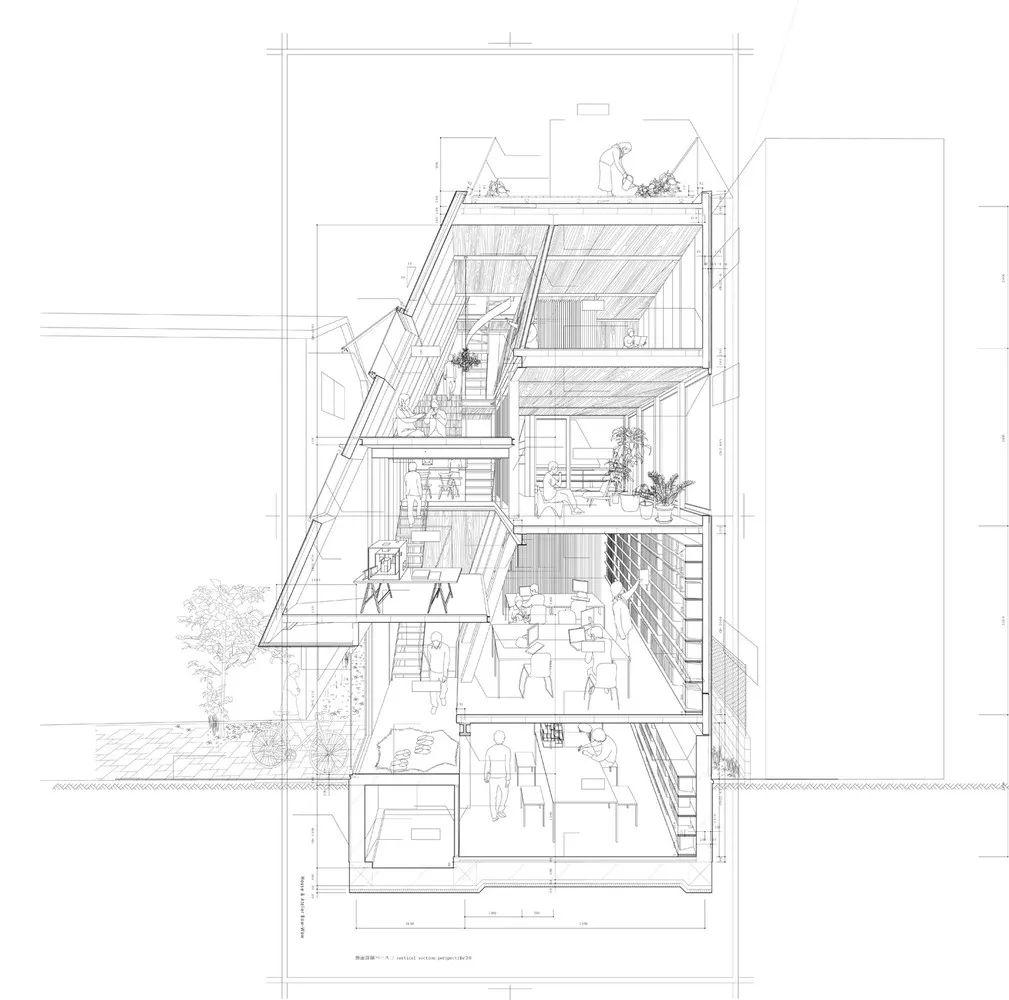

Jingqiu 除了这些城市空间项目,犬吠还做了很多小型住宅项目,例如:Kus House (2003)、House & Atelier Bow-Wow (2005)、House Tower (2005)等等。它们通常是小尺度的,位于日本本土,并且设计都基于犬吠对“行为”、当地环境因素和居住于其中的人们的生活的充分了解。请问犬吠在设计小住宅和公共空间时,都有着哪些不同或共通之处?它们是相互独立的研究项目吗?又或是,这些项目都遵循某种共同的思考和探索路径呢?

Jingqiu: You also have house projects, such as Kus House (2003), House & Atelier Bow-Wow (2005), and House Tower (2005). Those projects are small scale, mostly in local Japan, and based on a fully understanding of "behavior" of local environmental factors and life of people who live inside. What are the commons and differences when you design the house projects and the urban projects? Are these researches independent from each other or are there any overarching thoughts or questions behind them?

Kaijima 本质上说,我们的思考,从小住宅到大型公共建筑,都是延续的。例如《东京制造》是在探索东京各种有趣且有着混合功能的建筑。而在小住宅方面,我们通常有很好的客户,想在生活方式中表达他们的哲学观,其叙事同我们的设计也有着紧密的联系。

Kaijima: Basically, it's a continuous process from the small houses to the large public buildings. Our attitude is the same. Like Made in Tokyo, we found very interesting mix-use or hybrid-use buildings in Tokyo. We also have very nice clients who want to express, create some lifestyle that express their philosophy. Each individual and their narratives are very related to our design of the house.

举个例子,有的客户有很多藏书,所以想要很棒的书房,我们的设计就会建立在这样的需求之上;在另一个例子中,妻子擅长烹饪,一方面,家庭成员们既希望拥有共享空间,另一方面,他们又不想总是见到彼此,因此,我们想到创造一个有着三个层次的空间,使他们可以感觉到彼此的存在,同时在视觉上又互不打扰。我们总是会认真聆听使用者的想法,尽量让建筑和空间围绕这些对于居住环境的特别感知而展开。

Some people want to have very nice study room and they have a lot of books. They want to keep the study room with books and the design will be based on this. In another case, the wife is very good at cooking. The family members really want to share the house but don't always want to see each other. Then we design a space that has three layers, so they can feel each other's presence without seeing each other. We always hear people's intentions and then bring the kinds of special sensibilities of living conditions into buildings and spaces around them.

当然,作为建筑师,我们有很多关于空间的想法可以实现客户的需求,但归根结底,类似“我们想要一起共度在家的时光,却不想总是看到彼此”这样具体的、来自居住者的想法,才是我们设计的根基。

Of course, as architects, we have many ideas about space to realize what they want. But words and intentions we heard from them, "we would like to spend time at home together, but we do not want to see each other always" something like that, become the ideas of the space.

在犬吠设计的大大小小五十多个住宅项目中,每个项目的背后都有人们关于居住的特别愿景和意图。这些想法也教会我们了解人们是如何生活的,以及他们希望如何生活。极具活力的生活环境给了我们相应的素材和自由,让我们能够重新思考:如何使人们更积极地使用公共空间。与此同时,我们在小住宅中获得的关于居住的经验也在公共空间中得到了测试。

Amongst the fifty or so small houses that Bow-Wow has designed, each of them has a special wish or intention by the client. During the process, we received many ideas how people could live, how people want to live. This kind of dynamism in living conditions also provides us the freedom to reimagine how people could be more active in public domain. We also test the kinds of ideas that we got from single house projects in public spaces.

我们对参与公共空间的人们的声音一直保持开放的态度,我们很自信,这样做能为设计带去源于使用者自己的新想法和新意图。

We're very open to hear from many people who participate in the public space. We're also optimistic about bringing these new intentions to the public space for users.

比如,当政府希望建造一个广场,他们通常会对这个广场应该如何被建造或被使用没有什么想法,这时候,我们就希望听到来自当地人的声音。后者不同的意见将使广场本身的功能更加综合。这一点如果仅凭市政部门,有时是无法做到的,但不得不说,市政部门很擅长组织人们的集会。可是除了此种类型的集会,人们还可以有更多其他不同的集会方式。

For example, when the government or municipality has an idea of making a square, but unfortunately, they do not have any idea or methodology of how the square or the plaza should work. That's why we need to hear the voices on how the square will be operated from the local people. These voices create hybridized functions that the municipality is unable to imagine sometimes. But the municipality is good at gathering people. Besides the kind of gathering, there are many other different gatherings too.

Jingqiu 您能进一步谈谈犬吠是如何在不同项目中倾听民众声音的吗?

Jingqiu: Can you tell us a bit more your methods of gathering opinions from the people or how you test them in various Bow-Wow projects?

Kaijima 这往往取决于不同的语境。通常情况下,我们会尽量直接跟人们交流,有时市政部门也会通过调研收集人们的想法。不管如何,我都认为,在地跟人们直接见面、交谈、观察是相当重要的。在现场的时候,我们通常会发现一些已经存在的活动、新活动和“行为的种子”。Kaijima: It depends on the context. Basically, we prefer the chance to hear voices directly. Sometimes, municipalities collect opinions from surveys for us. But I feel that it is important to visit, meet, talk to people, and observe. In this way, we could find several examples of similar conditions, maybe there could be some 'seeds' for creating new activities or enhancing existing activities.

有时我们也会组织工作坊并邀请大家参加,以收集信息。这些工作坊在很大程度上扩展了市政部门的思路和想法。目前,日本的市政部门和议会行政人员的想法相对老旧保守,他们需要来自民众的新想法,而这些工作坊恰恰对于改变行政人员的思维模式有着很大的帮助。

Sometimes, we open workshop and invite people to gather information. These workshops are good ways to open the municipalities' minds. Currently, the problem with the municipality and the parliament is that that some of the politicians are a bit old-thinking and sometimes very conservative. For these politicians to change their minds, they need some inputs from citizens. These workshops have significances to make the changes happen.

如今日本有很多既有的东西,行政的人员往往只想遵循这些已有的、已稳定的东西来行事,如果这一情况不改变,由于缺乏新的想法以及同外界的沟通,我们的城市只会变得越来越糟。建筑设计有时候是为了维护原先稳定的社会以及活动,但新活动的产生,才能使建筑和社会不断的延续下去。

Maybe now, Japanese society has a certain level of established conditions, and some of the politicians just want to keep them the same. However, if these stable conditions remain unchanged, the situation will get worse and worse because of a lack of fresh ideas and an exchange with the outside. Sometimes architecture makes a good platform for the stability of the society, but they also need new activities to sustain our society.

Jingqiu 我们也很想知道,犬吠通常如何选择调研和设计的场所,特别是如今你们的许多项目都由城市转移到了乡村。这是因为你们发现在城市中,交流和对话比在乡村更难实现吗?

Jingqiu: We also wonder how you usually select your research sites. How do you usually find the spots for your projects, especially your transition from the urban to the rural contexts. Do you find it more difficult to create these kinds of conversation in the city than in the countryside?

Kaijima 城市和乡村是两种极为不同的情况。在乡村,周围有更多更便宜的资源,也有更多的空间,所以我们能更容易地创造新东西;在城市,例如东京,空间是很有限,我们每次都必须不断地投入财力。所以相比之下,乡村土地充沛,还有树木和很多其它的免费自然资源,使我们不必担忧资金的问题,这对我们来说是极好的。

Kaijima: I would say these two conditions are very different. In the rural area there are more resources around and more spaces that are very cheap. Therefore, it is easy to make new things. In Tokyo, there are very limited spaces and we must pay every time. In rural areas we do not have to worry about the payments because the land is abundant and there is forest, trees and so many resources that are easy to obtain without any payment. This is really good.

也许在未来,通过向乡村学习,我们可以进一步在城市语境中实现新的想法。比如,为什么不能在公园里种植经济树木用于砍伐呢?也许通过跟市政部门沟通,我们可以在城市中,在东京,建立“森林俱乐部”。人们可以通过会员制,自行砍伐树木,用以建造房屋和家具,这样一来,整个社区都会因之收益,人与人,人与城市的对话也能逐渐建立起来。

Maybe after learning from the rural area, the ideas can be put into the urban contexts in the future. For example, we might ask the municipality for permission to create a 'forest club' in Tokyo that allow people to cut trees in parks by themselves based on membership for creating buildings and furniture. It could create more enjoyments and conversations between people within and beyond the neighborhoods, between people and their living environments.

……

采访临近结束,我们聊起贝岛在城市或乡村语境中,对人与人,以及人与其居住的环境的思考。她批评道,全球化、设计产业化和建筑教育使我们被困在了某种固定思维中——建筑师们认为“只有一种生活方式,即一种与标准化的尺寸相联系的生活方式”——而对贝岛还有犬吠工作室来说,建筑的视野应当被放在更宽广的语境里,引发建筑师思考建筑背后和之外的东西,去发现“建筑背后的原因,整个历史和建筑工业,改变中的材料和技术,以及气候与环境” ,去思考 “人们生活的方式、文化和行为。”

Close to the end of the interview, my coworker and I contemplated Kaijima's words and thoughts related to people and their living environments, urban or rural. She criticized that globalization, building industry and education have "made us think that there is only one way of living—with standardized dimension." For Kaijima, as well as Atelier Bow-Wow, architects should try to think about what is behind and beyond buildings, to "discover why the building looks like this, also the history, the industry, the changing materials and the technology, the climate" as well as "the lifestyle, culture and behavior of people."

也许惟其如此,我们才能真正理解建造和设计的本质。

This is the way to consider design and architecture.

采访者注[1]:这些民族志学家包括柳田国男(Kunio Yanagita)、宫本常一 (Tsuneichi Miyamoto)、今和次郎(Wajiro Kon)等。

上一篇:激进派的先驱者、Superstudio创始人迪弗兰恰逝世

下一篇:赫尔佐格&德梅隆新作:堆叠体块创造灵动空间,Meret Oppenheim Hochhaus